Common Ankle Injuries: PTs Break Down What to Expect with Surgery and Rehab

with Mike McGowan, Windsor Physical Therapist

A common site of injury, whether it be in the general population or among athletes, is the intricate foot and ankle complex. The most common ankle injuries we see in the clinic, outside of your typical ankle sprain, are ankle fractures and Achilles tendon injuries, which include tendinitis (inflammation or irritation of the tendon), tendinosis (scarring, thickening, or hardening of the tendon) or a full tendon rupture.

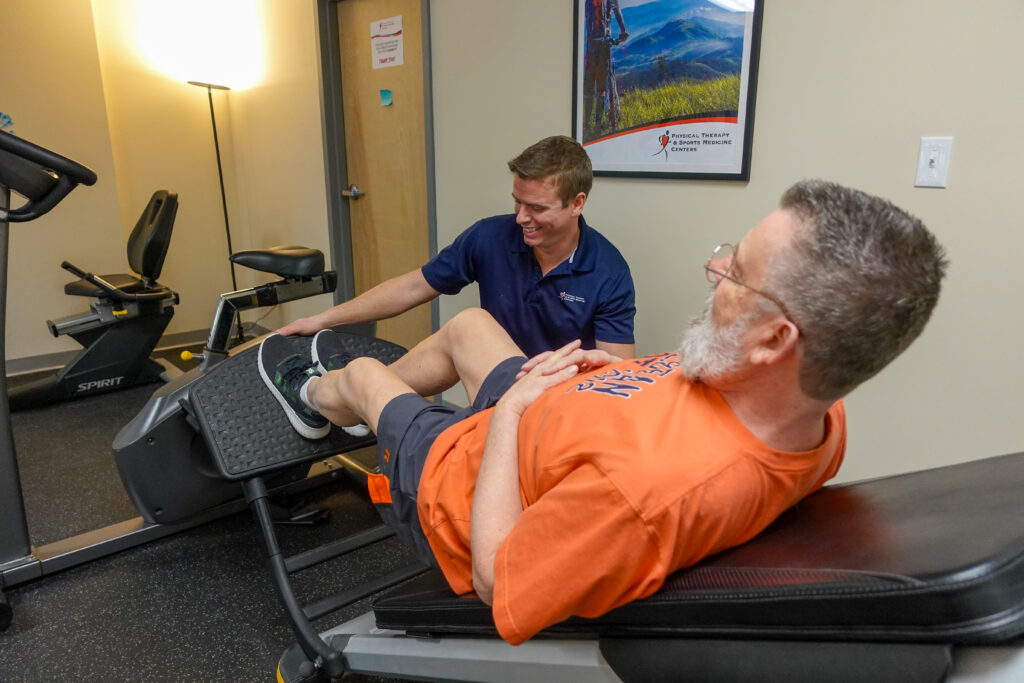

Physical therapists often work in coordination with orthopedic surgeons when severe injuries require surgery. Recently, PTSMC clinicians met with Dr. Thomas McDonald, an orthopedic foot and ankle specialist and surgeon from Orthopedic Associates of Hartford, to discuss how to achieve their common goal of getting patients back to their pre-injury levels of function.

What to expect after experiencing an ankle fracture

Let’s start by looking at ankle fractures, which can range in severity.

Ankle fractures can be broken down into two categories: stable and unstable. A stable fracture means the joint is not out of place, and you can usually put weight on it. An unstable fracture means the joint is out of place and often requires surgery and a recovery period before weight can be put on it. Typically, the more bones that are broken, the worse the injury and the more unstable the joint is.

Depending on the severity of the fracture, the location and other factors, there are a number of ways a surgeon might approach repair. One relatively new technique Dr. McDonald uses is a fibular nail to stabilize a post-surgery ankle fracture patient, which is less invasive and gets the patient back on their feet much quicker. Following surgery, physical therapists will work directly with surgeons to create a timeline and rehab program to help patients progress safely and appropriately towards full recovery. Following surgery using a fibular nail, Dr. McDonald recommends having the patient bearing weight by three weeks post-operation. Once weight-bearing is tolerated, the goal in physical therapy is to restore mobility and gently introduce muscular strengthening and joint motion by introducing the recumbent bicycle.

Interestingly, the faster a patient is using a bicycle during rehabilitation, the better their prognosis for rehabilitation.

As the rehab progresses further, the patient can begin recreational walking around the 12-week period. Following that, all activity that is athletic in nature is re-introduced 4-5 months post-op. This is generally speaking – of course, the more severe the injury and involved the surgery, the longer the rehab time. Both the surgeon and the therapist remain in communication throughout the therapy program, continuing to monitor progress and set goals and expectations with the patient.

What to expect after experiencing an Achilles tendon injury

The root of all evil when discussing lower leg injuries, especially Achilles injuries, plantar fasciitis, and any non-specific heel pain, is a tight gastrocnemius (one of the calf muscles). When the muscle is inflexible, the response to certain forces acting upon that muscle are unable to respond as well, which can ultimately lead to injury.

One common injury within the athletic or “Weekend Warrior” crowd, but otherwise still seen in the general population, is an Achilles tendon rupture. The surgical process for fixing an Achilles tendon rupture has evolved from a long, vertical incision to a small, horizontal incision at the top of where the tendon begins. An apparatus is then used to reattach the Achilles tendon. This leads to less scarring and happier patients.

Post-op, the patient begins with a week of rest, followed by a follow-up with the physician to clean the wound and introduce the Controlled Ankle Movement (CAM) boot and partial weight bearing.

Goals for physical therapy following an Achilles rupture are slow and conservative, especially in regard to “passive” range of motion and manual therapy. Passive range of motion is when the physical therapist stretches the patient without any effort from the patient. This typically occurs somewhere between weeks 6-10, and is commonly paired with strengthening the muscles on the outside of the ankle. This time period is the “danger zone” for recovery, so the patient needs to be careful to avoid excess strengthening through plantar flexion (pointing the toes).

Week 10 and beyond, the goals can be transitioned to full strengthening with gradual return to function within the 12-16 week range. At this point, heel lift inserts are progressively lowered, the patient begins weight-bearing as tolerated and “active”range of motion can be initiated, meaning the patient moves and stretches the joint without help from the physical therapist.

It’s important for patients to remember that it often takes over a year to re-establish single leg plantar flexion strength to perform a heel raise – so don’t get discouraged! The healthcare team of the orthopedic surgeon and physical therapist will always have the patient’s safety in mind, including setting reasonable expectations and making sure progress doesn’t come at the cost of future health.